Welcome to another edition of Ill-Behaved Women, where I like to share the bold, brash women I’ve discovered while researching Florida Girls, my fictional story about a troupe of models who toured the U.S. during WW2 and beyond to promote a discount drugstore. There was just such a troupe, and they—like mine—went all the way to California.

But first, a quick note about The Queenpin Chronicles series. I have wrapped up the trilogy with Havana Girls, sending Thelma and the rest of the gang to the next mafia hotspot, Cuba. This one’s a dual timeline told from only two points of view—Thelma’s and a character you haven’t seen since book 1, Imogene Fuchs’s daughter.

In a weird way, this was my original vision for the first book. Not as a dual timeline situation with only two POV’s, but the idea of a character from the future who discovers this story. Maybe because that’s how I felt as I researched, like I was uncovering real stories from the past. That’s how alive these characters are to me.

That said, once I made the focus of the book the “Poster Girls” (the real touring troupe), I purposefully did not research the actual women. This is a made up story wherein the characters take on the Tampa mafia, and I didn’t want anyone to resemble those very real people. I did, however, strive to create characters and circumstances that were true to life, grappling with the issues women would’ve faced.

That red hot mama…

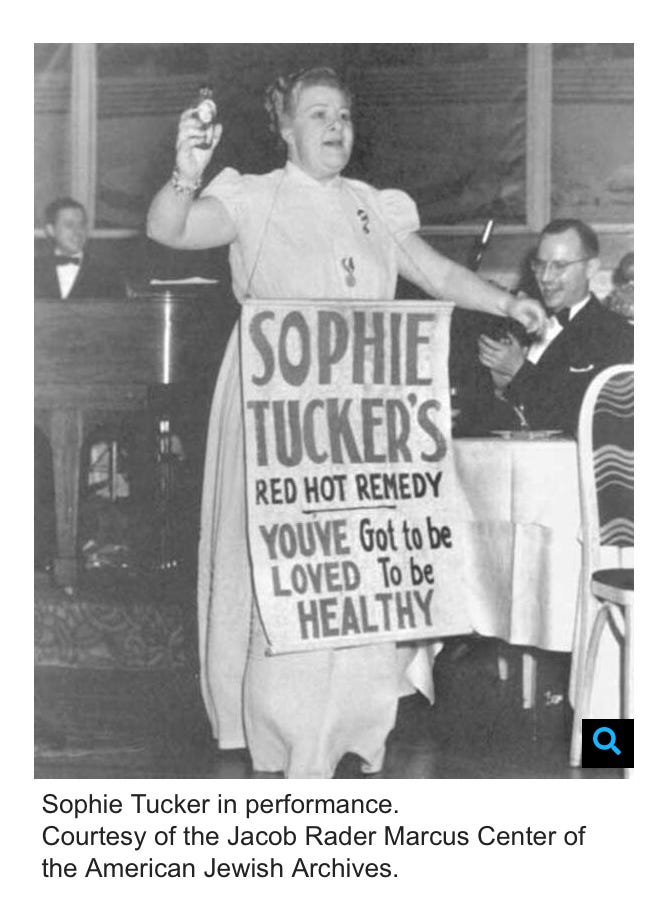

Sophie Tucker is a real-life character who appears in a Las Vegas nightclub scene with mob boss Sal Giancarlo and our heroine Thelma Miles, while the rest of the girls go to see Liberace (at his very real breakout performance). We’ve all heard of Liberace, but what about Sophie Tucker, the vaudevillian who billed herself, "The Last of the Red Hot Mamas"?

Tucker had a successful forty-year career in show biz, but I’d never heard of her until I started looking into historic records of performers in Vegas. (Side note, I found so much of interest in Vegas during this time, and related so hard to building a big splashy something out of a desert nothing—see, American Lady Creature, my first memoir—that of course I sent the girls back to Vegas for book 2. But I digress…)

Born Sonya Kalish in 1886 to a Jewish family in Ukraine, Sophie immigrated with her parents to the United States as an infant. The family settled in Hartford, Connecticut, where they ran a successful kosher diner and rooming house. In her autobiography, Some of These Days, Tucker recalls “the thrill” of waiting on Yiddish theater greats. According to Tucker, her mother believed that marriage, having babies, and helping her husband get ahead were career enough for any woman.

“I couldn’t make her understand that it wasn’t a career that I was after… I wanted a life that didn’t mean spending most of it at the cookstove and the kitchen sink.”

By the time she was a teenager, she started singing for tips at the restaurant, where she discovered her big, brassy voice. At 16 she married her first husband, but not long after her first and only child was born in 1906, she left her son with her parents along with a note declaring, “I have decided to go into show business. I have decided that I can do big things.”

Standing 5 feet tall and weighing over 145 pounds, Tucker struggled to get stage time until she started performing comically risqué songs and finally, at the insistence of her manager, donning blackface. She was, he said, "so big and ugly" she’d never get onstage otherwise.

The night her luggage didn’t arrive changed everything.

Tucker performed as herself, telling the audience, “You-all can see I’m a white girl. Well, I’ll tell you something more: I’m not Southern. I’m a Jewish girl and I just learned this Southern accent doing a blackface act for two years. And now, Mr. Leader, please play my song.”

Her act soared.

Strutting the stage in her flamboyant dresses and feather boas, Tucker belted out bluesy torch songs one minute and told bawdy jokes the next. No topic was off limits. She joked openly about sex, men, and her full figure at a time when women were expected to be demure.

When vaudeville declined in the 1920s, Tucker took her act to nightclubs and became the biggest star in the Roaring Twenties, commanding an unheard-of weekly salary of $5000 in an era when most families lived on $2000 a year.

In addition to sending money home, Tucker used her economic independence to help many of the prostitutes who lived in the same rooming houses as she. By 1945 she’d established the Sophie Tucker Foundation, supporting causes that ran the gamut from the Jewish Theatrical Guild to the Negro Actors Guild, and the Catholic Actors Guild,

Ultimately, however, she believed her economic independence that doomed her marriages (she went on to marry two more times). As she put it:

“Once you start carrying your own suitcase, paying your own bills, running your own show, you’ve done something to yourself that makes you one of those women men like to call ‘a pal’ and ‘a good sport,’ the kind of woman they tell their troubles to. But you’ve cut yourself off from the orchids and the diamond bracelets, except those you buy yourself.”

Her Jewish heritage became problematic in Europe, and once again, Sophie changed up her act. Returning to the States, she became a hit on the new medium of radio with her own show and sassy catchphrases. When the Great Depression left many of her musician friends out of work, she put her money and fame to good use, opening her own night club specifically to employ struggling jazz artists. Sophie rode out the hard times of the 1930s like she always did—with moxie, dirty jokes, and chutzpah.

In the 1940s and 50s, Sophie transitioned to film roles, stealing scenes in movies like Honky Tonk and Broadway Melody of 1938. She was featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1955, which hailed her as a show business legend. In her 70s, an age when most stars faded away, Sophie launched a whole new cabaret act in Las Vegas revues with her racy jokes and songs. "I've been 30 for years," she'd quip.

In other words, her material hasn’t necessarily aged well. But the ageism and internalized misogyny that pervaded her experience didn’t keep her from doing her thing. Interestingly, throughout her life she insisted, “I’ve never sung a single song in my whole life on purpose to shock anyone. My ‘hot numbers’ are all, if you will notice, written about something that is real in the lives of millions of people.”

Sophie kept performing almost to the end of her life, doing her final show just months before passing away from lung cancer in 1966. "Haven't you heard?" she reportedly joked on her deathbed. "This is the time I get top billing!"*

From burlesque to Broadway, vaudeville to Vegas, Sophie Tucker blazed her own bawdy path to stardom. With her razor-sharp wit, big voice, and take-no-prisoners attitude, the "Last of the Red Hot Mamas" left an indelible mark on show business. Here's to Sophie Tucker.

How about you?

Had you ever heard of Sophie Tucker?

What people from the past have surprised you?

How do you feel about books that combine real-life figures with fictional ones?

Until next time!

I had heard of Sophie Tucker. Her name is linked in my mind with a joke she told in a recorded performance I heard many years ago.

"I was in bed with my husband Ernie, and he said to me, 'Soph, you got no tits and a tight box.' I said, 'Ernie, get off my back.'"