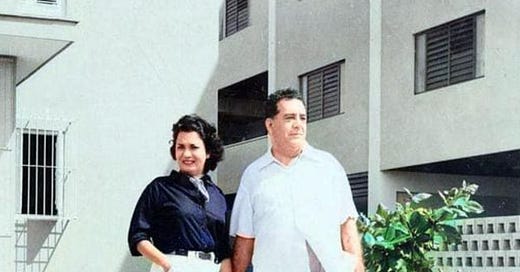

First Lady of the Tropicana, Ofelia Fox

FOX’S LAVISH LIFE, REVOLUTIONARY FLIGHT, AND RADICAL VOICE

My debut novel, Florida Girls, has been out for (one week shy of) a year, and I’m wrapping up the third book in the trilogy with Havana Girls, out June 26.

As I like to do in this space, I’m featuring a woman who lived life on her own terms—Ofelia Fox, part owner of Havana’s Tropicana.

…the women who stood beside the men in those glamorous rooms were not accessories but witnesses, chroniclers, and often co-conspirators.

In the golden years before Havana fell to revolution, the Tropicana nightclub wasn’t just a glittering throne of rhythm and rum. It was a temple. Its high priestess? Not the dancers, not the crooners, not even the mobsters pulling strings in the wings. The woman with the real voice, the backstage access, and the sharpest gaze in the room was Ofelia Fox, wife of Tropicana co-owner Martin Fox, and later a Miami radio legend who refused to stay silent when everything around her burned.

Born Ofelia Suárez in Havana in 1923, she was smart, striking, and sharp-tongued. By the time she met Martin Fox, a man already waist-deep in the complicated waters of Cuban nightlife and politics, she’d published poetry and built a reputation as a literary force. Their marriage was more than a social alliance—it was a collision of glamour and guts. Martin ran the Tropicana; Ofelia made sure its legacy reached far beyond its neon palm trees.

In its heyday, the Tropicana was a playground for the international elite, from mobsters like Meyer Lansky to movie stars like Ava Gardner. Carmen Miranda, Nat King Cole, and Celia Cruz performed under the open sky. And in the audience? Dignitaries, dictators, and the occasional spy. Ofelia, in her role as hostess, held court with the same poise whether she was entertaining Hollywood royalty or brushing shoulders with underworld financiers.

We all know what became of the high life in Havana.

As Fidel Castro’s revolution gathered steam, the Tropicana became a symbol of everything the new regime wanted to dismantle: excess, American influence, and under-the-table capitalism. In 1959, shortly after Castro's troops rolled into Havana, Martin Fox fled to Miami, where he'd already sent money ahead in anticipation. Ofelia followed soon after.

It wasn’t an easy escape for the Cubans, many of whom left behind art, jewelry, and property titles to discover an unfriendly labor market. In the months leading up to the revolution however, Martin had been sending money out of the country while Ofelia reportedly helped smuggle valuables out of the country for others. That soft landing gave Martin the cushion he needed to start a bolita game in the U.S.—a numbers racket that helped them stay afloat in exile.

Following the Bay of Pigs in 1961, the mood among Cubans in Miami was dark. In response to her community’s despair, Ofelia began to write uplifting essays and poems in the style of José Martí. But she also asked her fellow exiles to reflect and accept responsibility for what had happened to their nation.

In a twist that shocked and delighted me, she recognized that the way to truly broadcast, her message was through radio. So, like Julia Child, she financed her own radio show and became the first female Cuban radio commentator in the United States. Her program was part news, part memoir, and all defiance. Ofelia’s voice—poised, precise, unwavering—became a lifeline for other exiles trying to make sense of their lost home.

After Martin’s death in 1964, Ofelia eventually moved west, settling in Glendale, California with friend and fellow Cuban exile, Rosa Sánchez. They’d met at the radio station and formed a bond most now believe ran deeper than companionship. Ofelia never remarried.

But she wasn’t done telling stories.

In 2007, decades after she’d left Cuba, Ofelia’s memoir, Ofelia Fox’s Cuba: A Memoir of the Tropicana Days was published by Rosa Lowinger, an architectural preservationist and Cuban-American writer. The book—drawn from her poems, letters, and reminiscences—is a rare document, a first-person view of Havana’s lush, corrupt nightlife from the inside. It’s a time capsule—frank, stylish, and unapologetically political. Plus, it made a helluva backgrounder for Havana Girls.

What makes Ofelia’s legacy so compelling isn’t just the glamor, or even her survival of a revolution. It’s that she refused to become a relic. As the world moved on from the big-band Havana era, she kept insisting it mattered—that it had meaning beyond the nostalgia. That the women who stood beside the men in those glamorous rooms were not accessories but witnesses, chroniclers, and often co-conspirators.

In this way, Ofelia Fox belongs squarely in the pantheon of ill-behaved women who make history by telling their true stories—even if it means paying a high price.

She died in 2006 at age 82. But her voice, and the voice she gave to a generation of silenced exiles, still echoes.

SOURCES

Lowinger, Rosa. Tropicana Nights: The Life and Times of the Legendary Cuban Nightclub. Houghton Mifflin, 2005. https://www.rosalowinger.com/tropicana-nights

NPR: “In Exile, A Glamorous Queen of Havana's Tropicana”

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=10738552Los Angeles Times obituary: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-may-08-me-fox8-story.html

I'm blown away by what you have achieved with your beautiful set of books. Love the history and the focus on the real women behind the men. I wish you only the best, Trish